Health Management for our Dogs: Part 1

Escaping into the woods is one way Monty and I cope together, getting back to our “natural” habitat.

Frameworks & Rubrics

Dog trainers and other animal trainers alike have created a multitude of rubrics and frameworks to help them systematically work through the behaviors seen in our animal charges. Two such frameworks are the Five Freedoms and the Humane Hierarchy.

The 1965 Brambell Report first proposed The Five Freedoms of Animal Welfare in response to poor livestock conditions in the United Kingdom. However, these guidelines can be extrapolated to all captive animals. They recognize the animals’ inherent right to have:

Freedom from hunger and thirst

Freedom from discomfort

Freedom from pain, injury, or disease

Freedom to express normal behavior

Freedom from fear and distress

These guidelines brought farming forward and still remain as a solid baseline for many welfare-conscious animal caregivers. However, they are limited in their scope and aspects of care are lacking. These five freedoms are the bedrock of welfare, not welfare in its entirety.

The Humane Hierarchy was first developed by Dr Susan Freidman in a 2008 article, and is now the basis of many training plans, and is the basis of training ethics for some certifying organizations, such as the CCPDT. Many trainers have condemned the framework on both sides of the training spectrum: more heavy handed trainers consider the framework to be too lenient, and other trainers consider the inclusion of punishment in the framework to be too intrusive altogether.

I discussed the Humane Hierarchy in this blog post as well.

In short, these frameworks should not stand alone in a training plan. They are each individual parts of a multi-modal behavior analysis. However, one common factor stands out between the two: health is at the foundation of welfare. Any good training plan should at a bare minimum, consider the health of the animal first and foremost.

As we see in the Five Freedoms, welfare is more than just adequate food, water, and shelter. Many beloved housepets are well equipped with frequent access to food and water, and always have a roof over their head. Many of these same dogs receive yearly or twice yearly veterinary care. However, true welfare considers the animal’s species-specific needs and whole body health. For chronically under exercised, under enriched, and confused dogs, their welfare is lacking. Likewise, welfare is lacking for overweight, chronically ill, or painful dogs.

Why is this the case?

It is the unfortunate reality that veterinary staff members are under equipped and overworked to discuss each aspect of a dog’s care with each client. The average veterinary appointment is 15 minutes. 15 minutes to discuss your dog’s care with a healthcare professional once a year is insufficient. For this reason, many clinics have a necessary “get it done” attitude, leading to quick exams and distracted conversations, requiring the staff to pick their battles.

Let’s take the example of an older dog who has presented to her local veterinary clinic for a standard yearly exam. This exam often requires some bloodwork, a urine sample, a fecal sample, and a quick physical exam. The client has also asked for the dog’s nails to be trimmed. The dog is a little bit lame in her front leg, let’s say elbow arthritis, but the guardian hasn’t noticed it, as it’s a relatively subtle lameness. The appointment ends, and the veterinarian didn’t mention the lameness. Why is that?

The veterinarian notices that the dog is a little bit lame, and means to discuss it with the client. However, after they trim the nails, administer the vaccines, run the fecal, urine, and bloodwork in the clinic’s in-house laboratory, and they realize the dog has some elevated liver values, the conversation never gets around to the dog’s lameness.

The client brings the dog into the exam room, and a technician takes the dog’s history. The dog is laying down, panting and trembling in the exam room. When the tech brings her into the back treatment area, the dog puts on the breast, requiring another staff member to assist the first technician to bring the dog back. They lift the dog onto the exam table, where the veterinarian does a quick check for any big, bad, or ugly masses, ensures the heart, lungs, eyes, ears, and teeth look good for the dog’s age, and then the veterinarian is called away to a pet that had a minor walk-in emergency. The two technicians bring the dog back to the client. The client has to wait for the veterinarian to be freed up from the emergency to have a chat. by the time the veterinarian is able to chat with the client, they’ve pushed into the next appointment time. The conversation is rushed, the veterinarian never saw the dog walk. Additionally, the lameness was not evident, as the technicians needed to encourage the dog to move throughout the clinic in the first place.

By the time the client notices the lameness a few months later, the clinic’s nearest appointment is a few weeks after that. By that point, the dog’s elbow arthritis has progressed and they are referred to a specialist. The specialist is booked out for a few months, and by that point, the dog is unable to walk. This scenario can be applied to many chronic, subtle or “less important” medical issues common in pet dogs. Who’s fault is it?

The Medical Industrial Complex

The blame lies in the medical industrial complex.

For more information about the MIC, I highly recommend this free webinar.

The medical industrial complex, or MIC, is defined as “… the extensive and interconnected network of entities involved in the delivery and financing of health care in the United States. This complex includes various stakeholders such as hospitals, doctors, pharmaceutical companies, and insurance providers, all of which play crucial roles in the provision and management of medical services. Originating from significant legislative efforts, such as the Hill-Burton Act in 1946, the medical industrial complex has evolved from small, community-based facilities to large corporate-run hospitals. Critics argue that the profit-driven motives of this complex often overshadow patient care, leading to rising costs and limited access to affordable health services.”

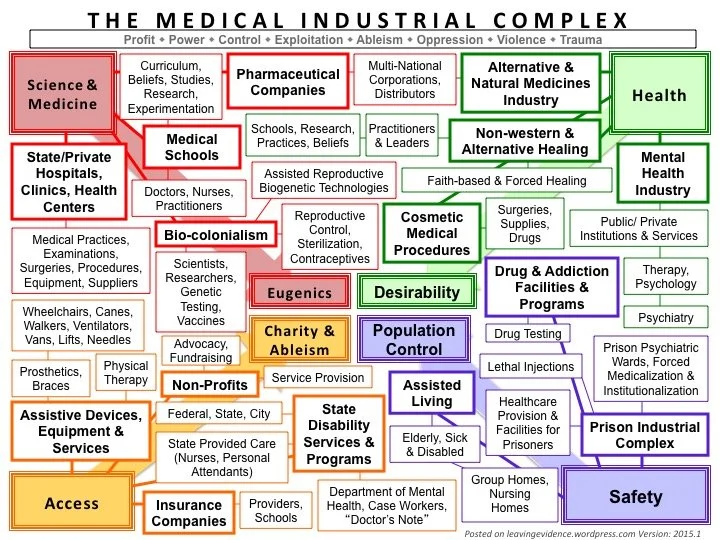

The medical industrial complex is vast, and is the natural progression of our late-stage capitalist world. This beautiful and frightening illustration perfectly sums up what is encompassed in the MIC. This is a human centric illustration, but the veterinary applications are not far off.

Falling victim to the medical industrial complex is an inherent issue of late stage capitalism, the time period in which we are all living. LSC defined by Merriam Webster as “the current stage of capitalism that began in the second half of the 20th century and that is characterized by globalization, the dominance of multinational corporations, broad commodification and consumerism, and extreme wealth inequality.”

Falling victim to the MIC or struggling to exist in late stage capitalism is NOT a moral failing of the vet staff, the client, or you. This is not the life humans or dogs were designed to live in. We are all learning to cope, survive, and thrive in this society. We and our dogs are in this together, and you, as the dog guardian, should not be held responsible for knowing the amount of knowledge the veterinary team has. You should not be expected to know every aspect of your dog’s care, see and recognize subtle signs of illness for what they are, and carry the burden of your dog’s health entirely on your own shoulders.

What do we do?

However, you are responsible for your dog’s health and wellbeing overall. This can mean scheduling more frequent veterinary appointments, bringing in behavior, fitness, or knowledgeable other dog professionals, or doing some of your own research. The most important thing, however, is working to do better when you know better. This raises three incredibly important points:

You are reading this article, which already sets you ahead.

You are reading this article on my website. I have quite a bit of veterinary experience, am a certified canine strength and conditioning coach, and can assist you with your dog’s needs as a behavior professional, fitness partner, or a medical liaison between you and your veterinary staff. If you and I aren’t the right fit, I have a cabinet of other trainers and resources that I can point you to.

There is so much here: self care, late stage capitalism, the medical industrial complex, mental health, physical health of you and your dog… This goes beyond a blog post.

This will be part one of a multi-part blog post series discussing our dog’s weights, why this is critically important, and how we can do better when we know better for this topic in particular.